Module 5: Profit from a rising share price

This module discusses potential profits and losses, explains how to choose between the different calls on offer, and looks at your choices once you have bought your call.

Module 5: Profit from a rising share price

This module discusses potential profits and losses, explains how to choose between the different calls on offer, and looks at your choices once you have bought your call.

If you think a company's share price will rise, you may consider taking (buying) call options.

If the share price rises, the call should increase in value, giving you the possibility of potentially unlimited profits. The higher the share price rises, the more money you make.

If the share price stays steady, or falls, the call will lose value. No matter how far the share price falls, the most you can lose is the premium you pay for the option.

Let's look at the following call option:

XYZ June $10.00 Call option @ $0.42

- the right, but no obligation to buy

- 1000 shares in company XYZ

- for $10.00 per share

- at any time up until the option expiry date in June.

- The option premium is $0.42 per share.

Buying a call option reflects a view that the share price will rise.

You can of course take advantage of a bullish view by buying shares.

There are several reasons why you might consider buying calls instead of investing in the underlying shares. Purchasing a call option:

We will consider each of these reasons in the next topic.

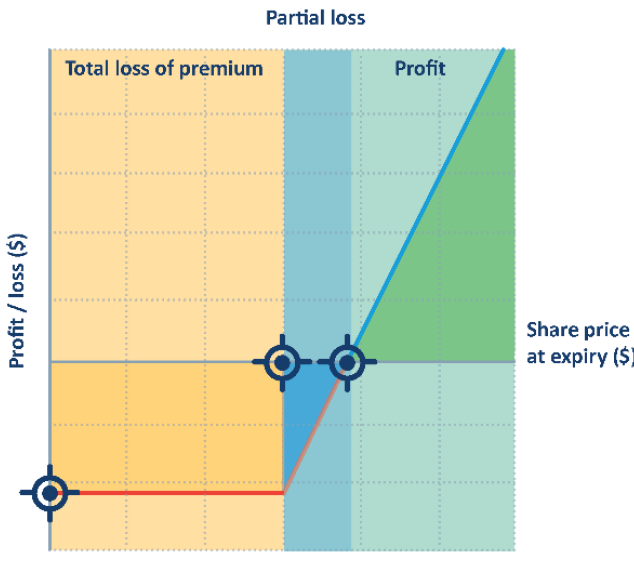

The most you can lose when you take a call is the premium you pay. You will make this loss if at expiry the share price is at or below the exercise price.

If the share price is above the exercise price, the option will have intrinsic value. The higher the share price is, the more the option will be worth.

The breakeven point is the exercise price plus the premium paid. At this point, the option is worth what you paid for it.

Above the breakeven point, you will make a profit - the higher the share price, the greater your profit.

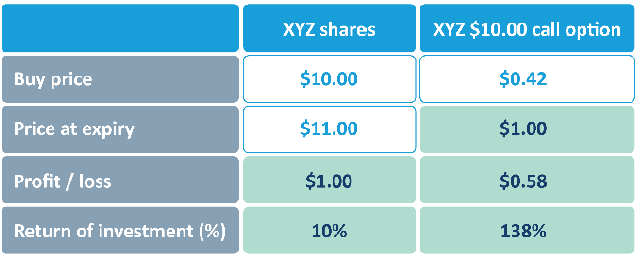

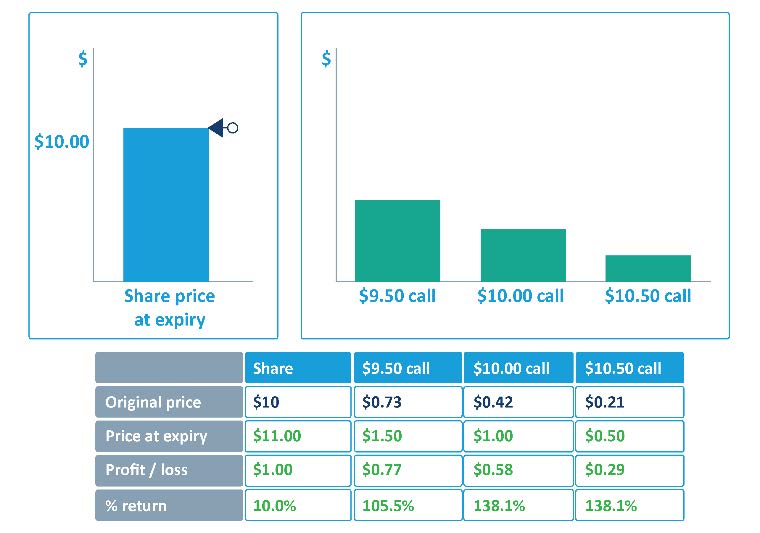

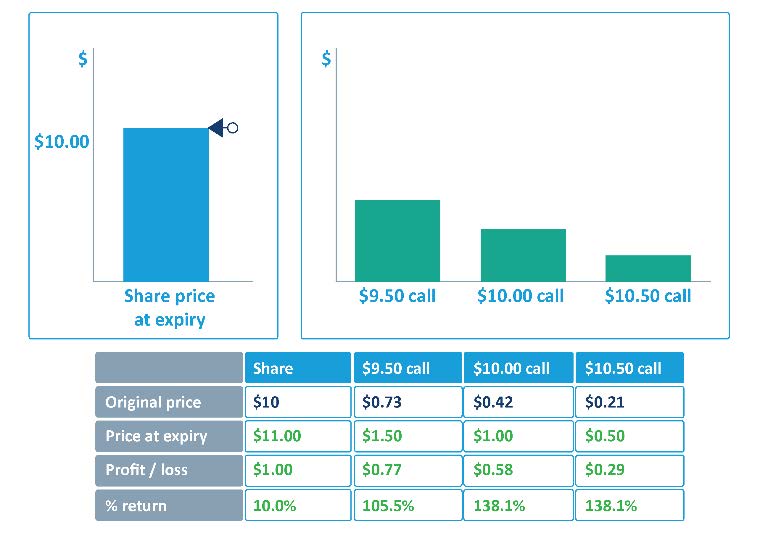

Leverage (also called gearing) means a relatively large exposure for a relatively small cost. A small movement in the share price results in a larger change, in percentage terms, in the option price.

Call options cost a fraction of the underlying shares.

1000 XYZ shares cost you $10,000, compared to, say, $420 for one June $10.00 call option.

If the share price rises, your percentage returns from the option are usually significantly more than the return from the shares. If the share price moves in the wrong direction, your losses in percentage terms will also be magnified.

You think the share price will rise over the next couple of months.

You consider two possibilities:

The share price has moved favourably, and leverage has increased your returns.

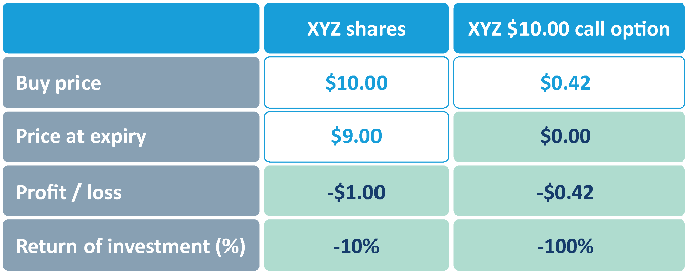

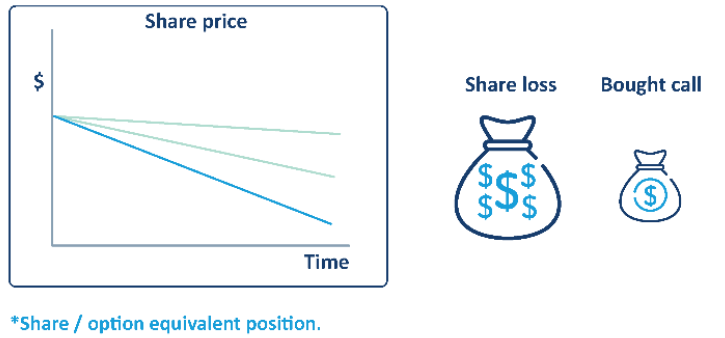

Leverage works both ways. If the share price falls, the call option will suffer magnified losses in percentage terms.

If the share price falls by $1.00, you will suffer a loss of 10% on the shares.

The $10.00 call will be out of the money, and expire worthless. Your loss is 100%.

It's important to be clear that leverage refers to changes in percentage terms.

In dollar terms, the change in the share price will be more than the change in the option price. However if you increase your exposure by buying more options the dollar amount loss may also be higher.

If the share price at expiry is below the exercise price, the call option will expire worthless - a loss of 100%.

In dollar terms, however, your total amount at risk is far less than if you buy the shares.

No matter how low the share price falls, the most you can lose is the premium, in this case $0.42.

If you buy XYZ shares, you have far more at risk. While it's unlikely that the share price will fall to zero - you can potentially lose $10.00.

When you buy a call, you lock in your maximum purchase price for the life of the option. No matter how high the share price rises, you have the right to buy those shares for the exercise price.

This enables you to defer your decision to buy, but lock in your purchase price at the time you buy the option.

You buy time - time to decide whether to proceed with the share purchase.

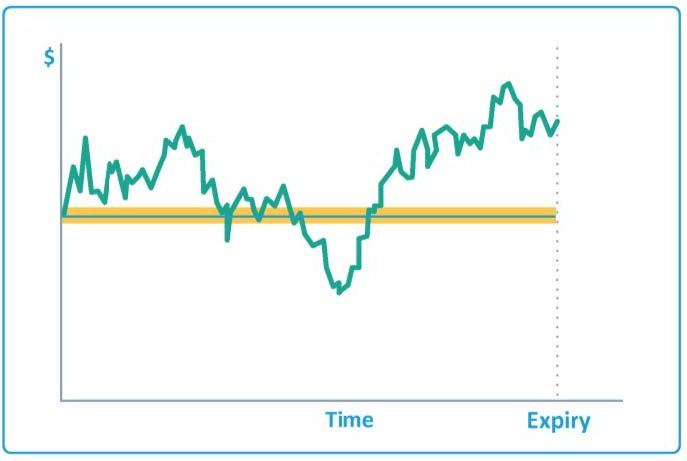

The main risk of buying a call is that the share price does not behave as you expect.

If the share price falls, or stays steady, the option will fall in value. If at expiry the share price is below the exercise price, the call will expire worthless.

A fall in volatility also hurts the bought call. If you buy a call and implied volatility subsequently falls, your position will be worthless prior to expiry - even if the share price has risen moderately.

Finally, time decay works against you. The premium you pay for the option includes time value. At expiry, the option consists only of intrinsic value. To make a profit, the share price must have risen far enough to cover the time value lost.

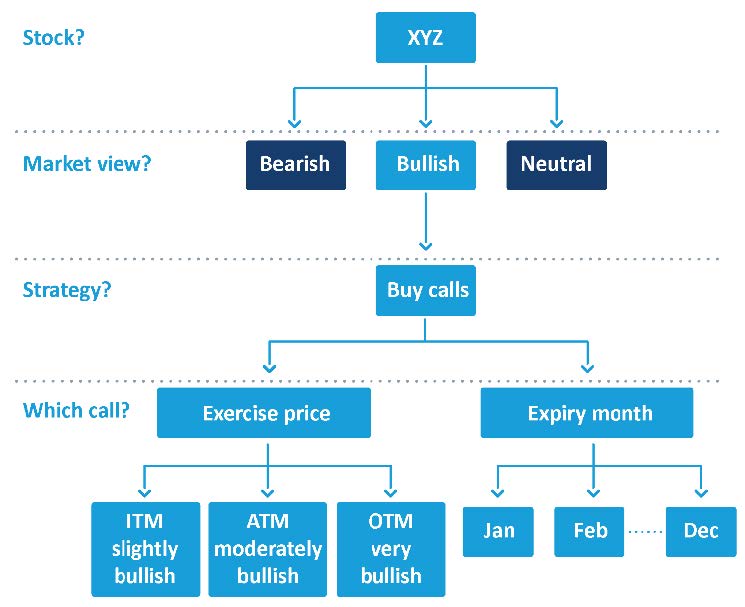

Once you have settled on the bought call strategy, the next step is deciding which call to buy.

You have a choice of exercise price and expiry month.

The decision involves weighing the benefits of each option against the option premium.

Assume XYZ shares are trading at $10.00 in early May.

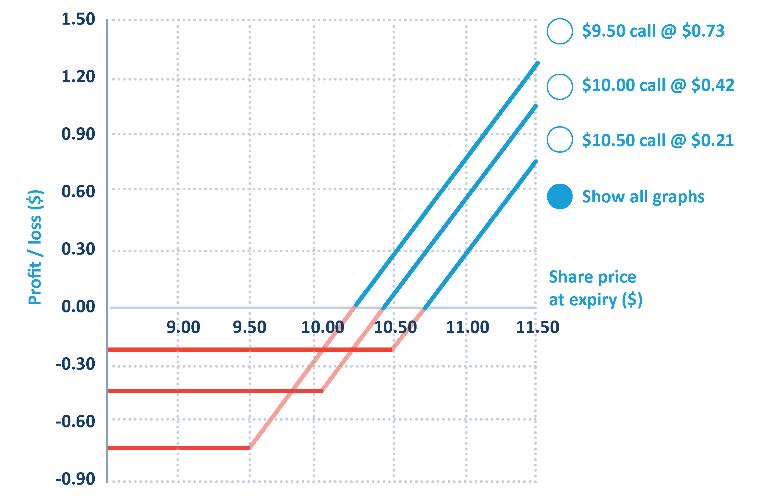

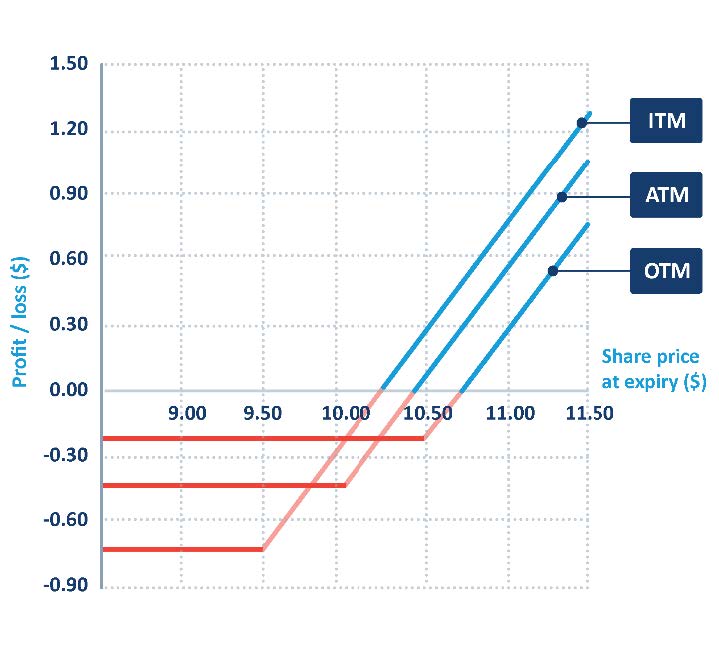

You consider the following calls:

The factors to consider include:

Generally, the lower the exercise price, the lower the breakeven point, and so the smaller the share price rise required for you to make a profit.

However, the lower the exercise price, the more expensive the option - and so the more you stand to lose if the share price falls.

The ITM option requires the smallest rise in the share price ($0.23) to breakeven, but if the share price falls, you have the most at risk.

The OTM option is the cheapest - but it needs a share price rise of $0.71 to breakeven. To buy this option, you must be extremely bullish.

The ATM option requires a move of $0.42 to breakeven. Its premium ($0.42) is between the $9.50 and $10.50 call in cost.

Although the $10.00 call is not the most expensive, it has the most time value. If the share price stays steady, the ATM option will result in the biggest loss.

Your choice of exercise price depends mainly on:

The more bullish you are, the more you can consider the OTM option. If the share price rises significantly, this option provides the most leverage.

If you are only moderately bullish, you may prefer the ATM or ITM option, as a smaller share price rise is needed for you to break even.

The OTM option is the cheapest, as it has the lowest chance of breaking even. You pay more for the ATM and ITM options - but have a better chance of making a profit.

There is no way of knowing what the share price will be at expiry.

However, you can work out what your profit/loss on the call would be, given any share price.

At expiry, your option will be worth intrinsic value, which is the difference between the share price and the exercise price. Time value will be zero.

Profit/loss = intrinsic value - the premium you paid.

If you bought the $9.50 Call @ $0.73, and at expiry the share price is $10.46:

Profit = ($10.46 - $9.50) - $0.73 = $0.23.

An option has a limited life, and the price rise you are looking for must take place by expiry - so you need to choose an expiry month that gives you enough time.

A longer term option gives you more time for the stock price to rise significantly and will hold its value for longer in the short term due to slower time decay in its early life.

However, the longer the term, the more the option will cost. As well as increasing the amount at risk, the higher premium also increases the breakeven point - the share price must move that much further before you make a profit.

Expiry month selection becomes a trade-off between the length of time you need for your strategy to succeed, and the cost of the option and time decay considerations.

So far we have looked at the result if you maintain your option position until expiry.

However you don't have to hold your position until the option expires - in fact most option positions are closed out ahead of expiry.

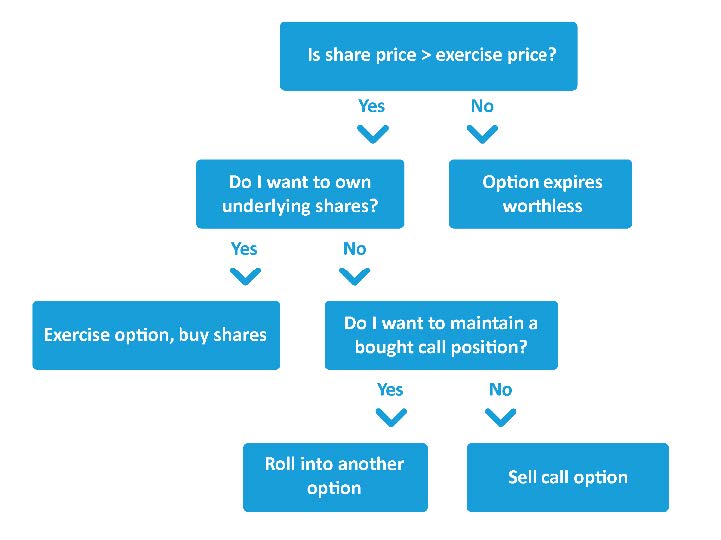

Once you have bought your call, you have a choice:

Unless you take one of these courses of action, the option will expire worthless.

If at expiry your option is in the money, but you don't want to exercise and buy the shares, you can sell the option.

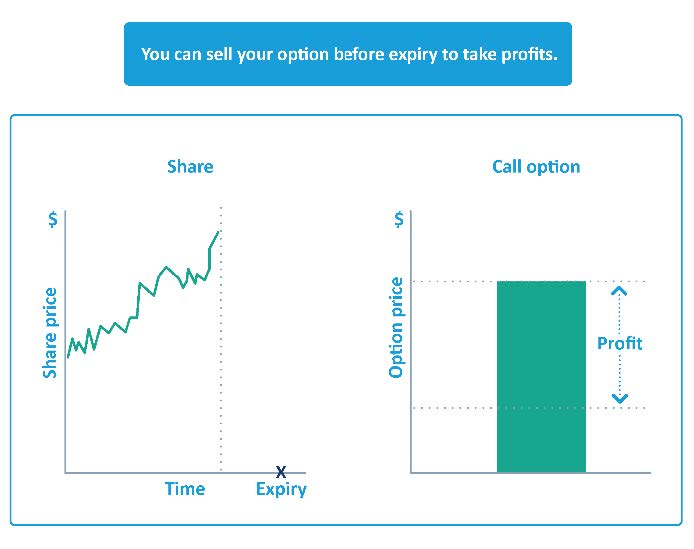

You don't have to wait until expiry to act - you can close out your position by selling on the market at any time.

Assume you have bought the June $10.00 call @ $0.42.

After two weeks:

You think the share price is unlikely to rise further, and want to take profits.

Selling the option gives you a profit of $0.26.

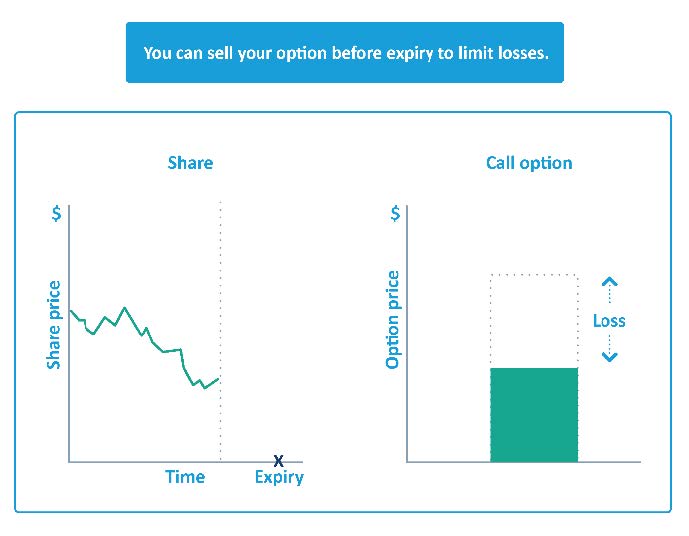

What if the share price has remained steady or fallen, and your option has lost value?

You can:

Although your option may be out of the money, it will still have time value, as there is time remaining until expiry.

Assume after two weeks the share price is $9.75, and your option has fallen to $0.23, which is solely time value. You think the share price is unlikely to recover.

Selling the option results in a loss of $0.19.

While it's never pleasant to take a loss, if you take no action and the share price does not recover, your option may expire worthless.

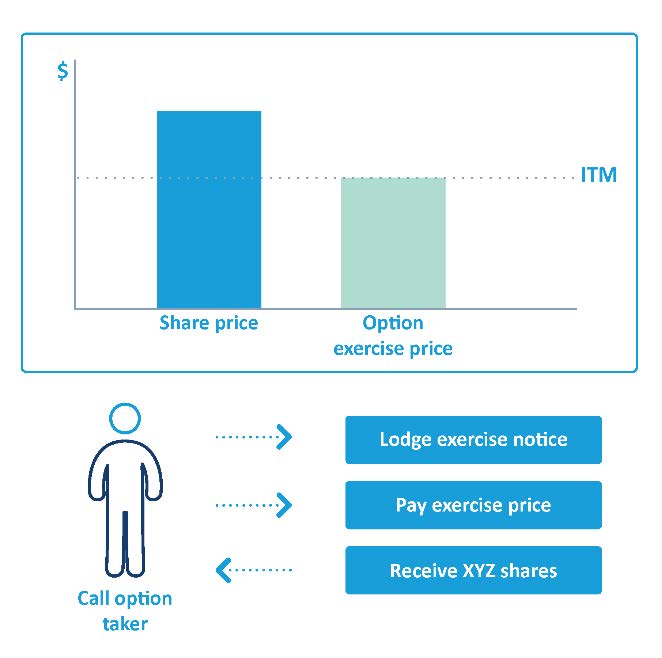

If you want to hold the underlying shares, exercising the call option may be appropriate (as long as the option is in the money).

It usually only makes sense to exercise a call at expiry. Exercising early means you are paying for the shares before you need to. When you exercise, you also sacrifice any time value left in the option.

The exception to this rule is when the stock is about to go ex-dividend and a call is deep in the money.

For more information refer to Early exercise of options.

The process of exercising is explained in Module 10: How options are traded.

With expiry approaching, you may think your view on the stock is correct, but you need more time.

In these circumstances you can roll your position.

Rolling means closing your existing position and simultaneously opening another position with a later expiry and/or different strike price.

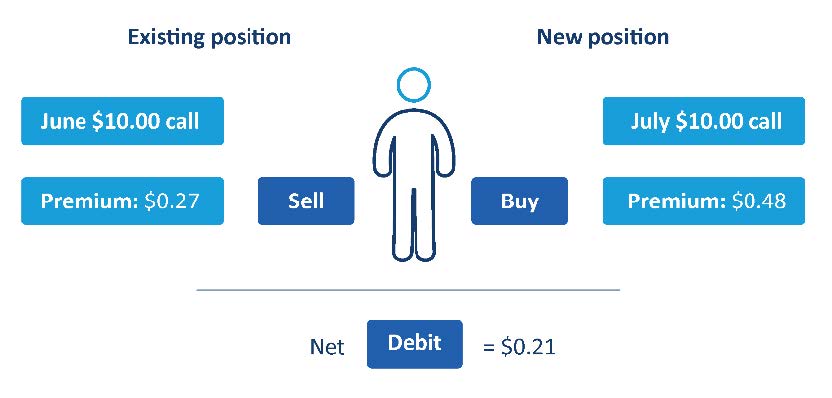

Assume you have bought the June $10.00 call @ $0.42.

A few days before expiry:

You believe the shares will rise over the next month. You roll your position by:

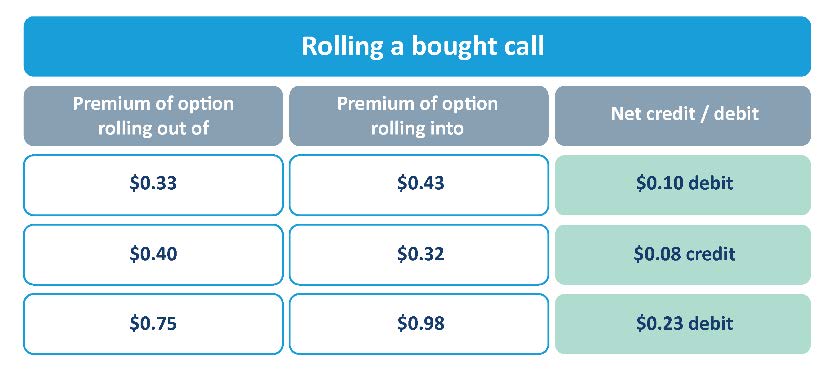

A roll may be done for a net debit (you pay money), or a net credit (you receive money).

If the call you roll to is worth more than the one you are rolling out of, the roll will usually be done for a net debit. This is typically the case if you are rolling to the same, or a lower strike.

If the call you are rolling to is worth less than the one you are rolling out of, the roll will usually be done for a net credit. This may be the case if you are rolling to a higher strike (though a roll to a higher strike will sometimes be done for a debit).

You can get a rough idea of what you can roll for by looking at the current prices for the two options.

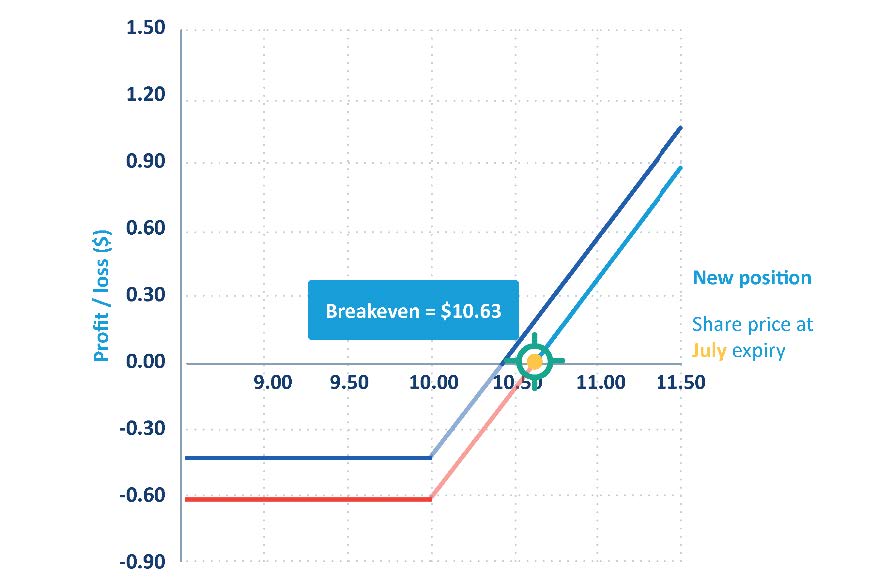

The premium you pay or receive, and the exercise price of the option you roll into, affect your breakeven point.

Rolling a bought call usually moves the breakeven higher - the share price must rise further for you to make a profit.

In the example, your new breakeven is $10.63:

New exercise price + total premiums paid = $10.00 + ($0.42 + $0.21) = $10.63.

Before rolling, think whether extra time is really what you need - or whether your initial view has proven incorrect. Committing more funds to an unsuccessful strategy may simply increase your losses.

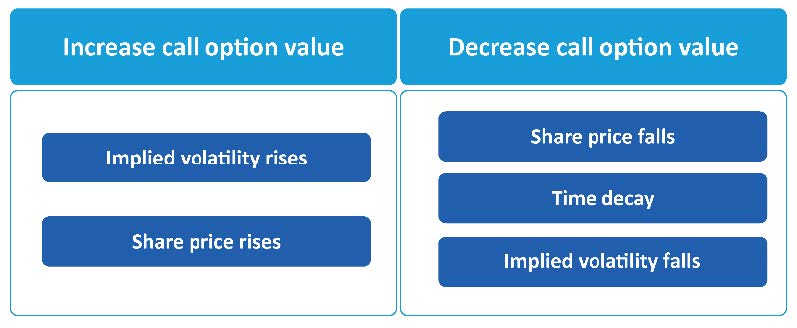

In any option strategy, you need to consider not just share price movements, but also the effects on the option of time decay and changes in volatility.

Buying a call reflects a view that:

Time decay works against the taken call.

The most you can lose when you buy a call is the premium paid.

Your potential profit is unlimited - the higher the share price rises, the greater your profit.

Your profit at expiry is the intrinsic value less what you paid for the option.

Your breakeven point is the exercise price plus the premium paid.

Practical examples of option strategies are given throughout this module.

Option prices used in the examples were calculated using a binomial pricing model.

Unless specified otherwise, prices are based on the following:

Keeping these assumptions constant in all examples should make it easier to compare the different strategies presented.